| Glossary Decision Tables Conditions Conclusions Expressions |

Iterations Sorting Environment Tables Code Tables Custom Decision Tables |

Decision Tests Decision Services Troubleshooting |

OpenRules customers build, test, deploy, and maintain business decision models using predefined and custom building blocks such as various decision tables and glossaries usually defined in Excel and maintained using Decision Modeling IDE. This guide lists major decision modeling building blocks with brief descriptions and examples of use. Use Ctrl+F to find a topic of interest. For more information see User Manual.

Glossary

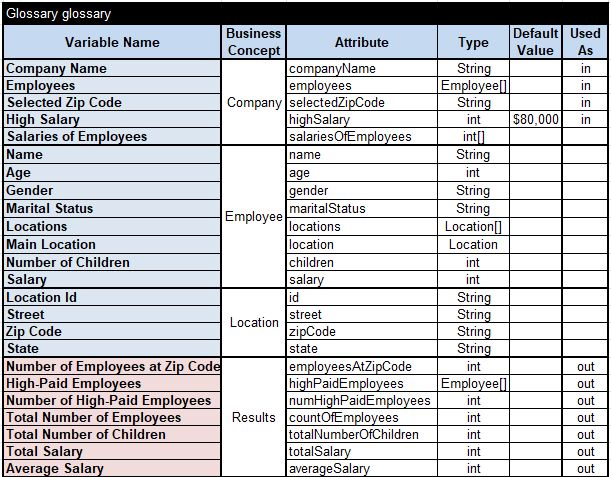

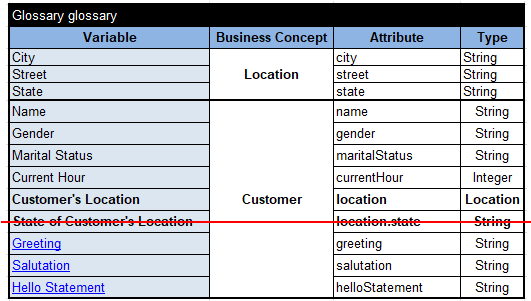

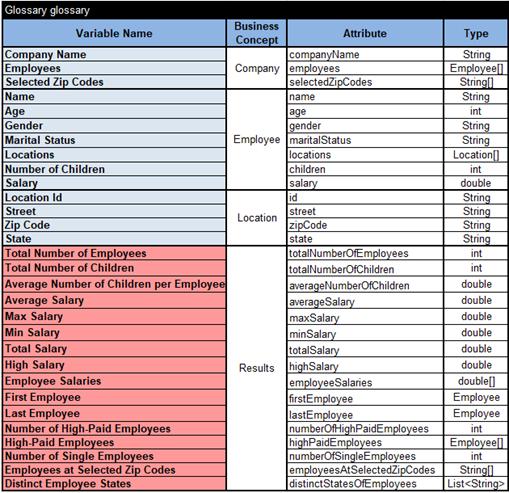

The table “Glossary” is at the heart of any decision model as it describes all business concepts and decision variables. It serves as a glue between business and technical parts. Here is an example Glossary from the sample project “AnalyzeEmployees”:

Usually, a business model has one glossary. But if it’s too big, you may split it into several tables of the type “Glossary” but with different names, e.g. glossaryClient, glossaryDriver, and glossaryCar.

The table “Glossary” contains 4 mandatory columns:

• Decision Variable

• Business Concept

• Attribute

• Type

The column “Decision Variable” should be always the first one as it defines the names of all decision variables exactly as they are used inside the decision tables. The names of decision variables should start with a letter or underscore and can contain only letters, digits, spaces, underscores, hyphens, and apostrophes (no other special characters allowed).

The column “Business Concept” should be defined as the second one and not contain spaces. It associates different decision variables with the business concepts to which they belong. Usually, you want to keep decision variables that belong to the same business concept together and merge all rows in the column “Business Concept” that share the same concept.

The column “Attribute” should be defined as the third one – it defines the technical names of decision variables that are used for the integration of the decision model with input/output objects. The names of the attributes cannot contain spaces and follow the “Camel” naming convention for Java and JSON attributes. Usually, business people should coordinate this column with their IT counterparts.

The column “Type” specifies the types of the decision variables. The typical types are:

- Integer or int – for integer numbers

- Double or double – for real numbers (or Float/float)

- String – for text variables

- Date – for dates

- Boolean or boolean – for logical variables with values TRUE (Yes) or FALSE (No).

You may add [] after the type, e.g. String[] to say that this is an array of strings. While it’s not important for business users to even know this, but these types are valid Java types. Actually, any Java types can be used in the column “Type”.

The column “Type” may even use the names of Business Concepts specified in this or other decision model glossaries or defined in 3rd party Java classes.

Your Glossary may contain various optional columns after the column “Type” – their order is not important.

The optional column “Description” provides a plain English description of the decision variable. It’s always a good practice to have the column “Description” in your glossary.

The optional column “Used As” allows you to set certain restrictions on how the decision variables are used by the decision model. If your glossary doesn’t include this column, then all (!) decision variables (except those defined in the Glossary’s formulas) will be included in the decision model output (response). This column may restrict the use of decision variables using the following properties or their combinations (via comma):

- in – defines a variable as the decision model’s input

- required – states that the input variable must have a value

- out – defines the variable as the decision model’s output

- const – defines the variable as a constant.

These properties can be listed in the column “Used As” separated by commas. Below is a description of the most useful combinations of these properties.

The property “required” triggers the validation of the decision variable. If the corresponding variable is undefined, OpenRules will produce an error at the execution time. A variable is considered undefined in the following situations:

- If the variable is defined using standard types such as String, Integer, Double, Boolean, etc. or custom business concepts defined in the glossary or Java, then it is undefined when its value is null

- If a numeric decision variable is defined using Java primitive types such as int, long, double, or boolean then it is undefined if its value is zero. In this cases the attribute “required” is ignored for undefined variables.

You may specify the default value for the potentially undefined variable in the column “Default Value”.

The property “out” tells OpenRules that this variable will be calculated within the decision model and should be included in the generated output such as the outgoing JSON structure.

If the cell of the column “Used As” is empty (no properties are defined), then the corresponding decision variable will be treated as a temporary variable that will not be included in the generated output.

The column “Used As” may be effectively used for security and performance improvement reasons. Only decision variables that are marked as out will be included in the output of the secure decision service and sent over the network back to the client.

The column “Default Value” defines the default values of the decision variables that are required as an input but come to the decision model undefined (null).

Some decision variables can be calculated inside the Glossary using formulas instead of attributes. They use a special indicator “:=” in the column “Business Concept”. For instance, the values for the two decision variables “Age in Years” and “Years of Service” are calculated by using formulas (Java snippets) specified in the 3rd column:

These variables will be automatically calculated as the number of years from today until “Date of Birth” and “Start Date of Service” correspondingly.

By default, the values of decision variables defined by formulas are being recalculated whenever these variables are used inside the decision service. However, you can notice that the above glossary specifies “Age in Years” as const in the column “Used As”. It directs OpenRules to calculate the value of the variable “Age in Years” only once at its first read and will never recalculate it again. Sometimes it could save recalculation time and improve the overall performance.

Note. If a decision variable is defined in the Glossary using a formula, it should not be used in DecisionTest tables. It also will not be included in the JSON response.

The optional columns “JSON Name” and “Business Concept JSON Name” allow you to use custom names with spaces in JSON tests instead of the names of business concepts.

The optional column “Domain” describes acceptable values (domain) of the decision variable. Only Rule Solver actually uses this column while in other products it is just for information.

Decision Tables

OpenRules uses classical decision tables which are in the heart of OpenRules from its introduction in 2003 and in general correspond to the DMN standard. OpenRules uses keywords “Decision” or “DecisionTable” to identify a table as a decision table.

Here is an example of a Single-Hit decision table identified by the keyword “DecisionTable“:

The first row after the keyword “DecisionTable” contains table name “DefineSalutation” that cannot include spaces and should be unique within the decision model. The second row uses the keywords “Condition” and “Conclusion” to specify the types of decision table columns. Instead of the keyword “Condition” you may it’s synonym “If”. Instead of the keyword “Conclusion” you may it’s synonyms “Action” or “Then”. All keywords are case-sensitive.

The third row contains the names of decision variables expressed in plain English (spaces are allowed). The columns of a decision table define conditions and conclusions using different operators and operands appropriate to the decision variable specified in the column headings.

The rows below the decision variable names specify multiple rules. For instance, the second rule can be read as:

“IF Gender is Female AND Marital Status is Married THEN Salutation is Mrs”.

All rules are executed one by one in the order they are placed in the decision table. For the horizontal (default) decision tables, all rules (rows) are executed in top-down order. For vertical decision tables, all rules (columns) are executed in left-to-right order.

The execution logic of one rule is the following:

IF ALL conditions are satisfied THEN execute ALL actions.

If at least one condition is violated (evaluation of the code produces false), all other conditions in the same rule are ignored and not evaluated.

Actions are executed only if all conditions in the same rule are satisfied. Conditions and actions with empty cells (or hyphens) are ignored.

There is a simple rule that governs rules execution inside a decision table:

The preceding rules are evaluated and executed first!

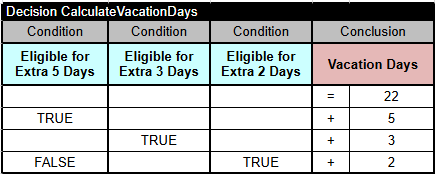

Multi-hit decision tables evaluate rules one by one and execute all (!) rules which conditions are satisfied. They are identified by the keyword “Decision“:

This table accumulates Vacation Days by adding all valid extra days.

The table “Decision” supports the following rules execution logic:

- Rules are evaluated in top-down order and if a rule condition is satisfied, then the rule actions are immediately executed.

- Rule overrides are permitted. The action of any executed rule may override the action of any previously executed rule.

A multi-hit table allows the actions of already executed rules to affect the conditions of rules specified after them.

Conditions

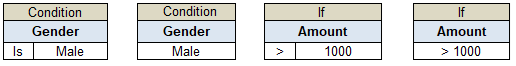

In most cases table conditions are specified by the keywords “Condition” (or its synonym “If”) in the second row of a decision table, e.g.:

If a condition has two sub-columns it means the first one used by operators like “Is” or “>” and the second one – by values like “Male” or “1000”. Conditions without sub-columns assume that the operator is “=” or “Is”. However, you may place an operator in the front of a value in the same cell, e.g. “> 1000”. For consistency reason it is recommended to use two sub-columns.

The condition cells can contain specific values like “1000” or “> 1000” but they also contain names of other decision variables or even expressions.

The following operators can be used for conditions to compare strings:

| Is | To compare two strings are the same. This comparison is case sensitive by default unless you changes it using the property “model.ignoreCase”. Instead of “Is” you also can write “=” or “==” (with an apostrophe in front of them to avoid confusion with Excel’s own formulas). Use the value null to check if a variable of type String, Date, Integer, Boolean, or any custom type is undefined. It will cause a syntax error if applied against a decision variable with a primitive type such as int, double, boolean. You may check the primitive variables against their default values (0 for int, 0.o for double, false for boolean). |

| Is Not | To check if two strings are not the same. This comparison is case sensitive. Synonyms: !=, isnot, Is Not Equal To, Not, Not Equal, Not Equal To. |

| Is Empty | Applied to check if a variable of the type String, Date, or a custom type like Customer is empty. The sub-column for the value should be TRUE/Yes or FALSE/No. |

| Contains | To compare if a decision variable contains certain values. For example, “House” contains “use”. The comparison is not case-sensitive. Synonym: Contain. |

| Does Not Contain | To compare if a decision variable does not contain certain values. For example, “House” doesn’t contain “user”. The comparison is not case-sensitive. |

| Starts With | To compare if a decision variable starts with certain values. For example, “House” starts with “ho”. The comparison is not case-sensitive. Synonym: Start. |

| Like | To check if a decision variable matches simple patterns with three wildcards: The percent sign (%) represents zero, one, or multiple characters The underscore sign (_) represents one, single character The character sign (#) represents one digit Examples: ‘ABCD” is like ‘ab%’ and ‘732-993-3131’ is like ‘___-___-____’ This operator is not case sensitive. Synonym: Is Like. |

| Not Like | This operator is opposite to Like. This operator is not case sensitive. Synonym: Is Not Like. |

| Match | To check if a decision variable matches standard regular expressions. For example, you can use the expression “\d{3}-\d{3}-\d{4}” to check if the content of the decision variable is a valid US phone number such as 732-993-3131. Synonyms: Matches. |

| No Match | To check if a decision variable doesn’t match a regular expression. For example, you can use the expression “[0-9]{5}” to check if the content of the decision variable consists of 5 digits like a valid US zip code. The condition is satisfied if it is not true. Synonyms: Not Match, Does Not Match, Different, Different From. |

You may control case sensitivity of comparison operators by setting the property “model.ignoreCase” to FALSE or TRUE (in the Environment table or in “project.properties”).

You may change case sensitivity of a particular operator by adding [Ignore Case] or [Case Sensitive] after the operator.

The following operators can be used for conditions to compare numbers:

| Is | To compare two numbers are the same. Instead of “Is” you also can write “=” or “==” (with an apostrophe in front of them to avoid confusion with Excel’s own formulas) |

| Is Not | To check if two numbers are not the same. Synonyms: !=, isnot, Is Not Equal To, Not, Not Equal., Not Equal To |

| > | To check a number represented by the decision variable is strictly larger than the number in the column’ cell. Synonyms: Is More, More, Is More Than, Is Greater, Greater, Is Greater Than |

| >= | To check a number represented by the decision variable is larger than or equal to the number in the column’ cell. Synonyms: Is More Or Equal. Is More Or Equal To, Is More Than Or Equal To, Is Greater Or Equal To, Is Greater Than Or Equal To |

| <= | To check a number represented by the decision variable is smaller than or equal to the number in the column’ cell. Synonyms: Is Less Or Equal, Is Less Or Equal To, Is Less Than Or Equal To, Is Smaller Or Equal To, Is Smaller Or Equal To, Is Smaller Than Or Equal To |

| < | To check a number represented by the decision variable is strictly smaller than the number in the column’ cell. Synonyms: Is Less, Less, Is Less Than, Is Smaller, Smaller, Is Smaller Than |

| Within | To check if a decision variable is within the provided interval. The interval can be defined as: [0;9], (1;20], 5..10, between 5 and 10, more than 5 and less or equals 10. Synonyms: Inside, Inside Interval, Interval |

| Outside | To check if a decision variable is outside of the provided interval. The interval can be defined as: [0;9], (1;20], 5..10, between 5 and 10, more than 5 and less or equals 10. Synonyms: Outside Interval |

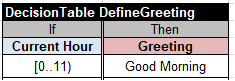

In conditions without operators OpenRules assumes the operator “Within” when an interval is specified. For example,

checks if the variable “Current Hour” is within the interval [0..11) assuming that 0 is included and 11 is not included.

OpenRules naturally supports date comparison with the operators =, !=, >, >=, <=, and < like in the following example:

Because different countries use different Date formats we recommend using the commonly understandable format “yyyy-MM-dd”. At the same time, OpenRules will recognize Date variables presented in the standard format specific for the majority of countries (using system locales). For example, the standard US date formats are “MM/dd/yyyy”, “MM/dd/yy HH:mm”, and “EEE MMM dd HH:mm:ss zzz yyyy”. We also recommend not to use the Date format when you define your dates in Excel: to avoid unnecessary conversion by Excel use a simple Text format.

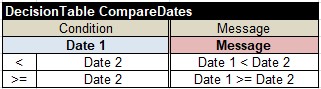

To compare two Date variables, you may do it as in the following decision table:

You may see more examples of how to use new Date operators by analyzing the sample project “HelloWithDates” available in the downloaded workspace “openrules.samples”.

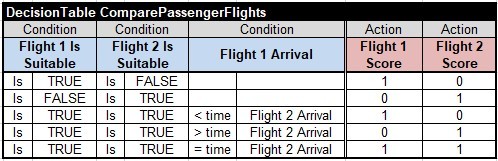

By default, OpenRules compares dates ignoring time. If you want to use time components of the Date variables, instead of the operators such as “<” you should use the operator “< time“, as in the table below:

If a decision variable has type “boolean” or “Boolean”, you can check if it’s true by using the following conditions:

You can use the following boolean values:

- True, TRUE, Yes, YES

- False, FALSE, No, NO

You also may compare two Boolean decision variables as below:

Checking if Decision Variables are Undefined

If you want to check if a decision variable is undefined, you may compare it with a special value null. Here are examples e.g.

Only decision variables of types String, Date, Integer, Double, Boolean, or any custom type can be compared with null. It you try to compare a decision variable of a primitive type such as int, double, or boolean with null, you will receive a syntax error.

For variables of the type String or Date you may use the operator “Is Empty”:

This condition of the type “ConditionBetween” check if the variable “Amount” is more or equals to 10 and less or equals to 20.

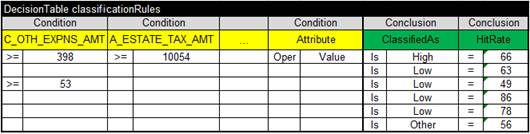

When your decision table contains too many columns it may become too large and unmanageable. In practice, large decision tables have many empty cells because not all decision variables participate in all rule conditions even if the proper columns are reserved or all rules. For example, here is a decision table taken from a real-world application that has more than 20 conditions (not all of them shown) with many empty rule cells:

To make this decision table more compact, instead of the standard column’s structure with two sub-columns

we may use another column representation with 3 sub-columns:

This way the above table will be replaced may with a much more compact table that may look as follows:

OpenRules provides necessary means to deals with conditions and conclusions defined on collections of decision variables such as arrays, lists, sets, or maps.

For example, this is a fragment of the decision table from the sample project “UpSellRules”:

Here the variable “Customer Profile” is a regular variable of the type String, and the first condition simply checks if the value of the variable “Customer Profile” is one of two strings “Bronze” or “Silver”. However, the variable “Customer Products” is an array of strings that identifies all products this customer already has. So, the second condition checks if this array includes product “Product 1” (the first rule) or if it includes the products “Product 1” and “Product 3” (the second rule). The third condition checks if this array doesn’t include product “Product 2” (the first rule) or if it doesn’t include the products “Product 6”, “Product 7”, and “Product 8” (the second rule).

The following operators can be used for conditions defined on one variable and one collection:

| Is One Of | For integer and real numbers, and for strings. Checks if a value is among cell values listed through a comma. Synonyms: Is One, Is One of Many, Is Among, Among. |

| Is Not One Of | For integer and real numbers, and for strings. Checks if a value is NOT among cell values listed through a comma. Synonyms: Is not among, Not among. |

| Starts With One Of | To compare if a decision variable starts with one of values listed through commas. For example, “House” starts with one of the values “hou, mo”. |

| Does Not Start With One Of | Compare if a decision variable starts with one of values listed through commas and returns TRUE is it DOES NOT. For example, “House” does not start with one of values “Mo, Wo”. |

The following operators can be used for conditions defined on two collections:

| Include | To compare two collections. Returns true when the first collection includes all elements of the second collection. Synonyms: Include All |

| Exclude | This operator is opposite to the operator “Include”. Returns true when even one element of the first collection is not present in the second collection. Synonym: Does Not Include |

| Intersect | To compare a collection with another collection. Returns true when the first collection and the second collection have common elements. Synonyms: Intersect With, Intersects |

| Does Not Intersect | Returns true when the first collection and the second collection do not have common elements. Synonyms: Does not Intersect With, Exclude All |

When these operators deal with strings, they are case sensitive. You may control case sensitivity of all these operators by setting the property “model.ignoreCase” to FALSE or TRUE (in the Environment table or in “project.properties”).

You may control case sensitivity of a particular operator by adding [Ignore Case] or [Case Sensitive] at the end of the operator.

If the decision variables do not have an expected type for the specified operator, the proper syntax error will be diagnosed.

Note that the operators Is One Of, Is Not One Of, Include, Exclude, Intersect, and Does Not Intersect work with values separated by commas. Sometimes a comma could be a part of the value and you may want to use a different separator. In this case, you may simply add your separator character at the end of the operator. For example, if you want to check that your variable “Address” is one of “San Jose, CA” or “Fort Lauderdale, FL”, the comma between City and State should not be confused with a separator. In this case, you may use the operator “Is One Of #” or “Is One Of separated by #” with an array of possible addresses described as “San Jose, CA#Fort Lauderdale, FL”. Instead of the separator “ #” you may use any non-alphabetic character after a space, e.g. “ ^”.

The above operators can you use the following items as their values:

- Constants, e.g., Bronze, Silver or Product 6, Product 7, Product 8 in the above decision table

- Decision variables, e.g., Var 1, Var 2, Const 2, Var 3

- A single decision variable that represents a collection defined somewhere else (in a test data or another decision table).

If the decision variable is a map (e.g. an instance of Java class HashMap) the following condition

will check if the map-variable “My Map” contains a pair (“key1”,”values5”).

Conclusions

Decision table conclusions are specified by the keywords “Conclusion” or its synonyms “Action”or“Then”, e.g.:

If a conclusion has only one column, the default operator “Is” or “=” is assumed.

The following operators can be used inside decision table conclusions:

| = | Assigns one value to the conclusion decision variable. Synonyms: Is, == |

| + | Takes the conclusion decision variable, adds to it a value from the rule cell and saves the result in the same decision variable. Synonym: += |

| – | Takes the conclusion decision variable, subtracts from it a value from the rule cell and saves the result in the same decision variable. Synonym: -= |

| * | Takes the conclusion decision variable, multiplies it by a value from the rule cell and saves the result in the same decision variable. Synonym: *= |

| / | Takes the conclusion decision variable, divides it by a value from the rule cell and saves the result in the same decision variable. Synonym: /= |

Note. Put an apostrophe in front of operators to avoid confusion with Excel’s formulas.

You may assign string using simple conclusion columns like in these decision tables:

You may assign numbers (integer, real, BigDecimal) using simple conclusion columns like in these decision tables:

You may use “” (double quotes) or “ “ in the action cells to assign an empty string or a space character to a String variable.

When you want to assign some values to decision variables that are collections (such as arrays or lists) you can use the following operators:

| Are | Assigns one or more values listed through commas to the conclusion variable that is expected to be an array/collection |

| Add | Adds one or more values listed through commas to the conclusion variable that is expected to be an array/collection. Synonyms: + |

| Add Unique | Adds one or more values listed through commas to the conclusion variable that is expected to be an array but making sure that these values are not present in the array/collection. Synonyms: +unique, +u |

There is a special conclusion/action types “Message” and “ActionPrint” for displaying messages directly from decision tables. For example, the following action displays the message “Employee is eligible to 27 vacation days”:

But if you want instead of hard-coded 27 days to display the actual number of vacation days already calculated in the decision variable “VacationDays”, you may use this action:

The expressions {{Name}} and {{VacationDays}} will be replaced with their actual values. By using “{{“ and “}}” around variable names you explicitly say that you want to use their values.

After the message, OpenRules will also print [produced by <name of the decision table>].

The action “Message” displays messages only when the property “trace=On” (in the file “project.properties”). If “trace=Off” and you still want to show certain messages, e.g. critical errors, you may use “ActionPrint” instead of “Message”.

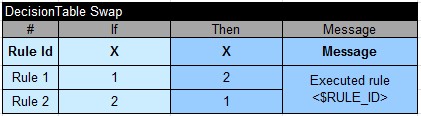

Sometimes, you want your message to refer to the rule that was applied. To do this, you may associate unique names with all rules in the column of the type “#” and then refer to these names in the Message column using $RULE_ID like in the following example:

The message will be shown as “Executed rules <Rule 1>” or “Executed rules <Rule 2>”.

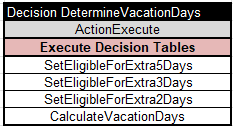

ActionExecute or Execute

This action executes all rules (decision tables) mentioned in this column in the top-down order. Here is an example:

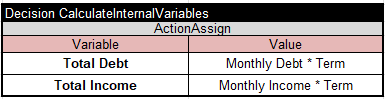

ActionAssign or Assign

This action assigns a value in the second column to the variable in the first column:

It is frequently used in multi-hit decision tables to assign values to multiple variables:

ActionAny

This action does nothing. However, if you want your action column to execute a Java snippet it can be done inside the column “ActionAny”.

ActionMap

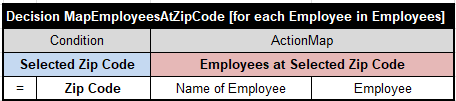

Here is an example of this action from the standard project “MapOfEmployees”:

This table iterates over an array of Employees. If the current Employee has the same Zip Code as the Selected Zip Code, then this Employee will be added to the map “Employees at Selected Zip Code” (the title of the second column) .

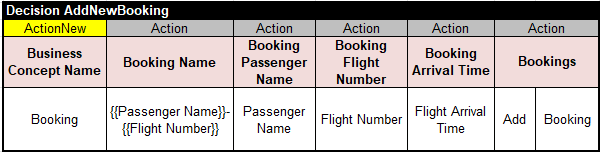

ActionNew

You may use this action to add a new object to a collection of objects. For example, you may create a new instance of the type “Booking”, assign values to its attributes, and add it to the collection “Bookings” using the following table:

Expressions

OpenRules allows you to use expressions (formulas) in the decision table cells. OpenRules supports the following expressions:

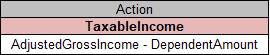

You may use naturally looking formulas that contain the names of your decision variable and traditional operation signs (+, -, *, /, and more) along with brackets to define the order of the operations. Here is a simple example:

That will assign a difference between values of AdjustedGrossIncome and DependentAmount to the variable TaxableIncome. Here is a more complex formula from the example “PatientTherapy” that calculates Patient Creatinine Clearance:

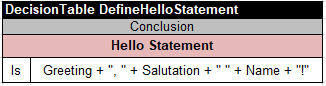

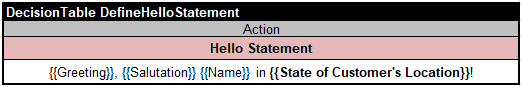

When your resulting decision variable has type “String” you can use the operator “+” to concatenate different strings (or even numbers). For example, this conclusion

will use the values of decision variable “Greeting”, “Salutation”, and “Name” (defined in the Glossary of the standard project Hello) to define a Hello Statement that may look like “Good Afternoon, Ms. Robinson!”.

Alternatively, you may explicitly use string interpolation by taking decision variable names the double curly braces, “{{“ and “}}”. It will allow you not to use pluses and quotations and simply write:

You also can use some simple functions like min(x,y) and max(x,y) like in the following actions borrowed from the standard project 1040EZ:

Here is a partial list of supported operators and functions:

| Feature | Syntax | Examples |

| Numbers | regular integer or real numbers | 10, 465.25, -25, 3.14 |

| Add | x + y | 3+2 |

| Subtract | x – y | 3 – 2 |

| Multiply | x * y | 3 * 2 |

| Divide | x / y | 3/2 |

| Power: x y | pow(x,y) | 5**2 |

| Negate | -x | -3 |

| Comparison | x < y x <= y x = y x <> y or x!= y x >= y x > y | 2 <> 3 [produces 1] 2 != 2 [produces 0] |

| Logical “and” | x and y | 1 and 1 [produces 1] 1 and 0 [produces 0] 0 and 0 [produces 0] |

| Logical “or” | x or y | 1 and 1 [produces 1] 1 and 0 [produces 1] 0 and 0 [produces 0] |

| Absolute value | abs(x) | abs(-5) [produces 5] abs(5) [produces 5] |

| Maximum between two numbers | max(x,y) | max(5,6) [produces 6] |

| Minimum between two numbers | min(x,y) | min(5,6) [produces 5] |

| Floor | floor(x) | floor(3.5) [produces 3] floor(-3.5) [produces -3] |

| Ceiling | ceil(x) | ceil(3.4) [produces 4] ceil(-3.4) [produces -3] |

| “π” | PI | The mathematical constant “π” |

| e x | exp(x) | exp(1) = 2.7182818284590451 |

| Rounding | round(x) | round(3.5) [produces 4] round(-3.5) [produces -4] |

| Square root | sqrt(x) | sqrt(9) [produces 3] |

OpenRules also supports many other operators and functions defined in the standard Java class Math.

Composing Decision Variable Names with qualifier “OF”

All decision variables used in decision tables or test tables should be defined in the glossary. However, you may compose new complex decision variables out of the existing ones without declaring them in the Glossary. For example, a sample project “HelloNestedLocation” has two business concepts “Location” and “Customer” defined in this Glossary:

To produce a greeting like: “Good Afternoon, Ms. Kaye in CA!”, a user could create the following table:

However, starting with Release 10 it is not necessary to define “State of Customer’s Location” in the Glossary. This expression uses a special qualifier “of” and OpenRules can automatically recognize that you refer to the “State” of the “Customer’s Location”. So, you may remove the proper variable from the Glossary. Similarly, you may write {{City of Customer’s Location}}.

The corresponding test data may be defined in the following table:

Instead of the qualifier “of” you may use a special divider “::“. For instance, in the above table you may write {{Customer’s Location:: State}} instead of {{State of Customer’s Location}}.

When your glossary includes multiple nested objects, the qualifier “of” and divider “::” may be used multiple times inside the expressions. For instance, the standard sample “DepartmentsEmployeesLocations” deals with the concept Department which includes decision variable Manager of the type Employee. So, you to refer to his/her salary inside a decision table, you may simply write “Salary of Manager of Department” or “Department :: Manager :: Salary”.

Functions on Collections of Objects

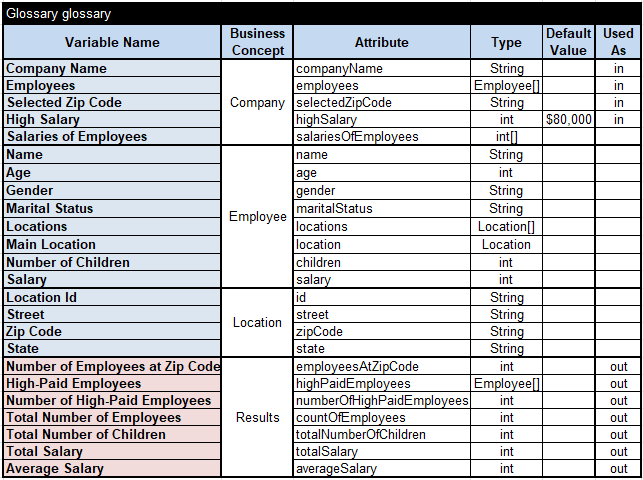

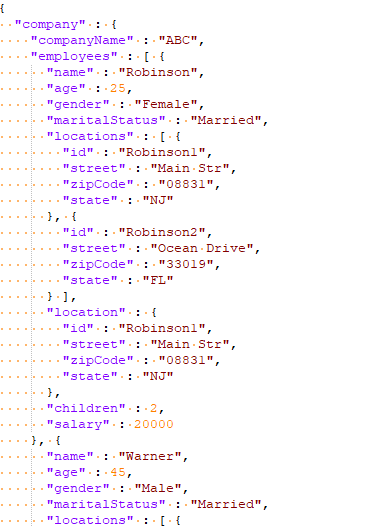

OpenRules supports various functions defined on collections of objects that allow you to avoid using iteration loops for the calculation of typical collection characteristics. A typical sample project “AnalyzeEmployees” is included in the standard installation. It has the following glossary:

The “blue” decision variables represent input information. As you can see, the concept “Company” contains an array “Employees”. The concept “Employee” besides various characteristics of one employee (Name, Age, Gender, Salary, Number of Children) includes an array “Locations” as an employee may live in multiple locations.

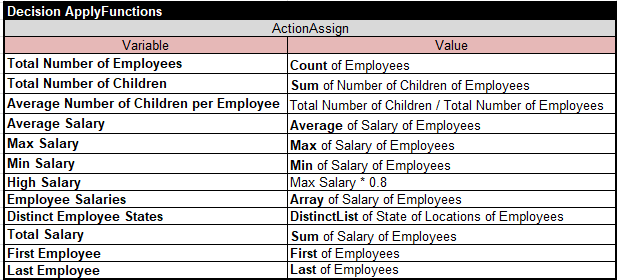

The “red” decision variables represent the output of this decision model which should calculate their values. Of course, it could be done using decision tables for “for-each” loops. However, it is much simpler to do it using the following decision table with “ActionAssign”:

As you may guess, the expression Count of Employees returns the total number of employees inside the collection “Employees”. The expressions Max of Salary of Employees and Average of Salary of Employees returns the maximum and average salaries among all employees.

The expression Sum of Number of Children of Employees calculates the total number of children for all employees.

The expression First of Employees returns the first employee in the array Employees, and Salary of First of Employees returns his/her salary.

The expression Array of Salary of Employees returns an array of all salaries for all employees (the array’s type is defined in the glossary as double[]).

As an employee may have residences in different locations in different states, we may construct a list of all states (without duplications) where employees have residencies: DistinctList of State of Locations of Employees. And we don’t need to use nested loops.

The first words inside these expressions are called functions and currently OpenRules supports the following functions on collections:

- Count of

- Sum of

- Max of

- Min of

- Average of

- Array of

- List of

- Set of

- DistinctArray of

- DistinctList of

- First of

- Last of

You may use combinations of such functions as in these examples: Average of Array of Salary of Employees and Count of DistinctList of State of Locations of Employees.

It is convenient to use these functions inside the “ActionAssign”.

You may use so-called “Java Snippets” inside decision table cells. They should start with a sign “:=” like in this example:

Similarly, the expression that calculates “Patient Creatinine Clearance” could be written using the following Java snippet:

In these examples, the ${Greeting} or ${Patient Age} refer to the value of the decision variable “Greeting” and “Patient Age”.

Java snippets allow users familiar with the basics of Java to write any arithmetic and logical formulas using valid Java expressions placed directly in the decision table cells but preceding by a sign “:=”. However, Java snippets are less friendly compared with simple expressions and business people may ignore this section.

To make Java snippets more readable to business users, OpenRules allows you to refer to the values of decision variables as ${variable name}. For instance, ${Amount} returns the value of the decision variable “Amount” with the type specified in the glossary (e.g., int or double). ${DOB} will return the actual date of birth. You also may refer to the entire business concept as ${business concept}. For instance, you may refer to the attribute “age” of the employee as ${Employee}.getAge().

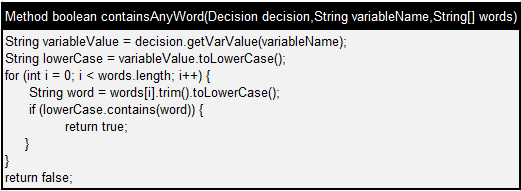

It’s possible to hide a Java snippet inside a special table of the type “Method”, e.g.:

Then we may call this method from this decision table:

Inside Java snippets you may use regular operators “+”, “-“, “*”, “/”, “%” and any other valid Java operators. You may freely use parentheses to define the desired execution order. You also may use any standard or 3rd party Java methods and functions, e.g.

:= Math.min( ${Line A}, ${Line B} )

If you want to use the value of a decision variable such as “Customer Location” inside a decision table cell, you may simply write “Customer Location” in this cell (with or without quotes). You even may simply write $Customer Location. While being more technical, Java snippets remove any limits from the expressive power of OpenRules. They allow using complex Java constructs like loops, functions, recursion, etc. They allow using any Java libraries created by your programmers or by 3rd parties.

Iterations

Real-world decision models frequently use collections of business objects such as employees of the company or charges inside a bill. OpenRules provides business-friendly capabilities to deal with such collections including arrays and lists of objects. They allow a user to define which decision tables to execute against a collection of objects and to calculate values defined on the entire collection.

Standard projects “AggregatedValues” and “AggregatedValuesWithLists” demonstrate how to iterate over collections of business objects. The business concept Employee is defined in the Java class Employee with different customer attributes such as name, age, gender, maritalStatus, salary, and wealthCategory. Another class Department defined the business concept Department that include employees defined as a collection of employees using an array Employee[] or ArrayList<Employee>.

We want to process all employees in each department to calculate such Department’s attributes as “minSalary”, “totalSalary”, “salaries”, “richEmployees” “numberOfHighPaidEmployees”, and other attributes, which are specified for the entire collection. Each employee within any department can be processed by the following rules:

Pay attention that we use here a multi-hit table of the type “Decision”, so all satisfied rules will be executed. The first one unconditionally calculates the Total Salary, Maximal and Minimal Salaries, etc. The second rule defines Employee’s Wealth Category, increases the Number of High-Paid Employees inside the department using the accumulation operator “+”, and adds this employee to the collection “Rich Employees”.

The above decision table will be executed “for each Employee in Employees” as defined in its signature row:

This iteration provides business users with an intuitive way to apply rules over collections of business objects (without the necessity to deal with programming loops).

When you need to iterate through arrays/lists of the basic types such as String[], int[], double[], etc. instead of the business concepts you may use the corresponding decision variables. For example, the standard project “ICD10” the object Claim has a decision variable “Diagnoses” of the type String[]:

In this project, we need to iterate through the array “Diagnoses” twice using the nested loops defines as follows:

Here the first decision table “IterateDiagnoses” iterates over the array of Diagnoses for the first time using a temporary decision variable “Diagnosis 1” and for the second time using temporary decision variable “Diagnosis 2” (they are defined only within these loops). To make sure that these variables are different, it uses an intermediate array “Already Selected Diagnoses”. For each unique pair (Diagnosis1; Diagnosis2) it executes the decision table “SearchCSV” that does a highly efficient search in the CSV file “ICD10Codes.csv”.

We can essentially simplify this decision model by using a special action-column “ActionNestedLoops”. Instead of the above table “IterateDiagnoses” we can use the following table:

You will get the same results but without an intermediate check for uniqueness of pairs (Diagnosis1; Diagnosis2). You can even remove “Already Selected Diagnoses” from the Glossary.

Sorting Collections of Objects

OpenRules allows you to easily sort arrays (or lists) of your business objects. You can use regular decision tables that define how compare any two elements of such arrays and add [sort <ArrayName>] at the end of its signature row. Let’s look at this sample:

This table is taken from the standard project “SortPassengers” that shows how to sort the array of “Passengers” using their frequent flier status and a number of miles. For each pair of passengers “Passenger1” and “Passenger2” it selects a preferred passenger in the last column of the type “ActionPrefer”. When the statuses of both passengers are the same, the number of frequent miles serves as a tiebreaker. When even the miles are the same, you may use “=” or “Same” (or any other word different from Passenger1 and Passenger2). There is no need to define “Passenger1” and “Passenger2” in the glossary that simply looks as below:

Here the array “Passengers” by itself is a decision variable defined inside the business concept “Problem”. The glossary does not include variables “Passenger1” and “Passenger2” as they are local variables used only inside the table “SortPassengers”. Their names are formed by the type “Passenger” of the array of “Passengers” plus the numbers 1 and 2.

This and a more complex project “FlightRebooking” can be found in the standard workspace openrules.samples. Another sample project “SortProducts” demonstrates how to sort arrays of objects defined in the Java class Product that need to be Comparable.

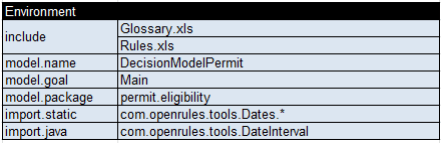

Environment Tables

The Environment table describes the structure of the decision model and specifies various properties used to build, test, and deploy a decision model. Here is an example:

This table states that our decision model includes files “Glossary.xlsx” and “Rules.xlsx”. Your model can use multiple xls– and xlsx-files located in different folders, and you can define them all in the Environment table relative to the file “DecisionModel.xlsx”. If your entire decision model is described in one Excel file, you don’t need to define the Environment table.

The property “model.name” specifies the name of the decision model as it will be known to the external world. This name should start with a letter and not contain whitespaces.

The property “model.goal” specifies the name of the main goal from the glossary that your decision model should determine.

The property “model.package” specifies the name of the internal Java package in which OpenRules will put generated Java files. It could be any name similar to “com.company.problem” but it should start with a letter and not to contain whitespaces.

The property “model.precision” specifies the precision of real numbers used to compare the expected and actualy produced results.

The property “model.endpoint” allows you to specify the endpoint URL when you deploy your decision model as a REST service. By default, OpenRules makes the endpoint based on the “model.name”, e.g. “vacation-days” based on the property “model.name=VacationDays”. You may replace it by adding a property such as “model.endpoint=calculate-vacation-days“.

The Environment table may specify the properties “import.java” and

“import.static” to add references to 3rd party Java classes. For example, the standard project “PermitEligibility” uses Java methods defined in the optional OpenRules package “com.openrules.tools” included in the standard installation. So, the proper table “Environment” for this project is defined as follows:

Here ”import.java” provides your decision model access to all methods of the class “com.openrules.tool.DataInterval” while “import.static” provides access to static methods of the class com.openrules.tool.Dates”.

Note. These and other project properties could be overwritten in the file “VacationDays/ project.properties”.

Tables with Java Code

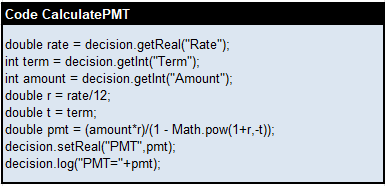

You can put your Java snippet inside a special table of the type “Code”, e.g.

This table uses a Java snippet (without “:=”). The same table may presented without Java:

Still, sometimes you may prefer Java to express complex not frequently changing logic and tables “Code” can be helpful.

You also may define a table of the type “Method” that contains a Java snippet that returns a value. For instance, you may call the following method

from this decision table:

Custom Decision Tables

OpenRules provides a very powerful rules templatization mechanism for the creation of custom domain-specific decision tables of virtually any complexity. You may define templates for your own condition and action columns and use them directly in standard OpenRules decision tables.

Condition Templates

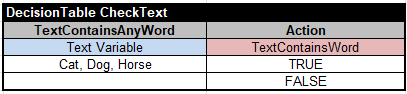

You may create a template for your own condition using a table with the keyword “TemplateCondition”. Let’s say you want to create a condition template called “TextConstainsAnyWord” and use it in the following decision table:

As you may guess, the condition in the first column should be satisfied only if the variable “Text Variable” contains at least one of the words Cat, Dog, or Horse. If yes, it will set the boolean variable “TextContainsWord” to TRUE, and otherwise to FALSE. The proper condition template may look as follows:

The second row calls the Method

containsAnyWord(decision,$COLUMN_TITLE,words)

defined as follows:

Action Templates

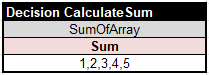

You may create a template for your own action using a table with the keyword “TemplateAction”. Let’s say you want to assign a sum of all array elements to another integer variable using the following decision table:

Here SumOfArray in the name of your custom action. Here is its implementation:

The table of the type TemplateAction allows you to put a Java snippet directly in the second raw without creating an intermediate Method or Code.

Using 3rd Party Libraries

Custom templates allows you to naturally connect decision tables with underlying Java packages. For example, a customer needed a decision model that dealt with complex spatial calculations, and they wanted to specify spatial relationships between various geographical entities like in the following decision table:

You may guess that for example the rule

can be read as “If the distance between an airport and a hospital is less than 250 mi, then Spatial Significance Score should be increased by 1”.

To support such decision tables with conditions of the type “ConditionEntityToEntity”, we created a new condition template:

After the keyword “TemplateCondition” the first row contains the name of the column that will be used as a condition inside any standard decision table.

The second row contains a snippet of Java code that implements this column. This particular template simply calls the static method “conditionEntityToEntity” of the Java class “GeoDatabase”:

GeoDatabase.conditionEntityToEntity (decision, mainEntityType, relationship, relatedEntityType, oper, value)

where parameters “mainEntityType”, “relationship”, “relatedEntityType”, “oper”, and “value” are described in the 3rd row, while the parameter “decision” is the default parameter available in any standard OpenRules decision table.

The Java class GeoDatabase for any two entities checks if the condition is satisfied. How it’s actually done is hidden from a business user inside the Java class, but the end users may freely use almost “natural language” expressions like “HRR+5” (meaning within 5 mi within this HHR entity) or “HRR Is Among 25 Closest to a Hospital”.

This project uses a large 3rd party library “JTS” for spatial calculations provided by Vivid Solutions. The proper dependencies were added to the file “pom.xml”. To make all these Java classes accessible from the decision model, the project uses the following Environment table:

You can find a complete implementation in the standard project “SpatialRules”.

Decision Tests

Test cases usually contain different combinations of input data along with the expected results. There are two way to define test cases: in Excel and in JSON.

Excel Test Cases

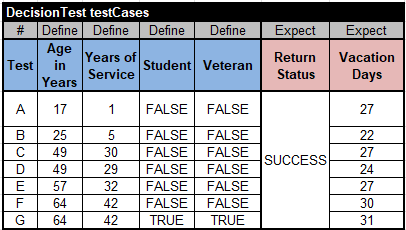

You may create a table of the type “DecisionTest” in Excel. Here is an example:

This table contains blue and pink columns. The blue columns with the keyword “Define” in the second row contain input data for decision variables “Age in Years”, “Years of Service”, “Student”, and “Veteran” defined in the Glossary. The pink columns with the keyword “Expect” contain the expected results such as “Return Status” and “Vacation Days”.

DecisionData Tables

The above table is simple and defines all variables directly by using their name. However, real-world test cases could be much more complex with inter-related references. One of such examples can be found in the standard sample project “AnalyzeEmployees” that deals with a Company that has many Employees who may live in different locations. Here is the proper Glossary:

You can use special OpenRules tables of the type “DecisionData” to represent test objects for different combinations of Company, Employee, and Location.

Let’s start with a DecisionData table “companies” that describes two companies “ABC” and “XYZ”:

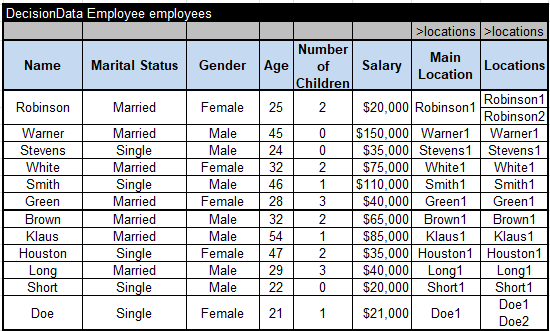

The second row of this table has a reference to the table “>employees” telling OpenRules that names like “Robinson” and “Warner” refer to the proper rows in the table “employees”. Here is the table “employees”:

The second row of the table “employees” has a reference to the table “locations” defined as “>locations” in the last two columns. When we use “Robinson1” or “Warner1” inside this column, OpenRules will try to find these names in the first column of the table “locations”. That’s how the table “employees” and “locations” are connected.

And, finally, the DecisionData “locations” defines all locations:

Using Data Tables for Testing

Now we can create DecisionTest table referring to the specified tables “companies”, “employees”, and “locations”. Here is how it can be done:

The second column “UseObject” allows you to associate the business concept “Company” with “companies[0]” (the first test case) or “companies[1]” (the second test case). The table “companies” defined the array with the same name. We may refer to its elements using indexes starting with 0. The object “companies[0]” is already linked to the proper employees from Robinson to Green. More than that, they have been already linked to the proper locations.

JSON Test Cases

When you plan to deploy your decision model as a REST service, you need to communicate with this service using JSON. OpenRules automatically generates JSON interface from your Excel test cases when you run “test.bat”. Here is a fragment and the first above test cases in JSON:

Decision Services

OpenRules Decision Manager takes a business decision model and converts it into highly efficient Java code and then automatically deploys it as a regular Java program on-premise, on-cloud, and even on smartphones without programming or complex configuration. OpenRules Decision Manager offers several integration and deployment facilities for converting your business decision models to operational decision services:

- Java API

- AWS Lambda Function

- MS Azure Function

- RESTful Web Services

- SharePoint Integration

- Amazon S3 Integration

- Docker Containers

- Apache Spark

- WAR Files for Application Servers

You may easily integrate your business decision model in any Java application, use it on any server like Apache Tomcat or IBM WebSphere, or deploy it on cloud as a decision microservice utilizing any serverless architecture provided by major cloud vendors such as Amazon, Google, Microsoft, or IBM. It is important to note that while in production your business decision model is used as a highly efficient decision service, you continue to maintain your decision model using OpenRules Explorer and Excel, and re-deploy it whenever necessary.

OpenRules empowers business users with an ability to assemble new decision services by orchestrating existing decision services independently of how they are built and deployed. The service orchestration logic is a business logic too, so it is only natural to apply the decision modeling approach to orchestration. To orchestrate different services, you may create a special Decision Orchestration model that describes under which conditions such services should be invoked and how to react to their execution results.

Troubleshooting

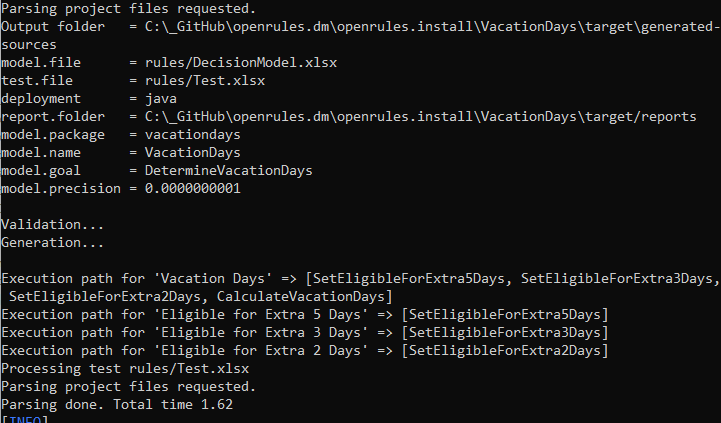

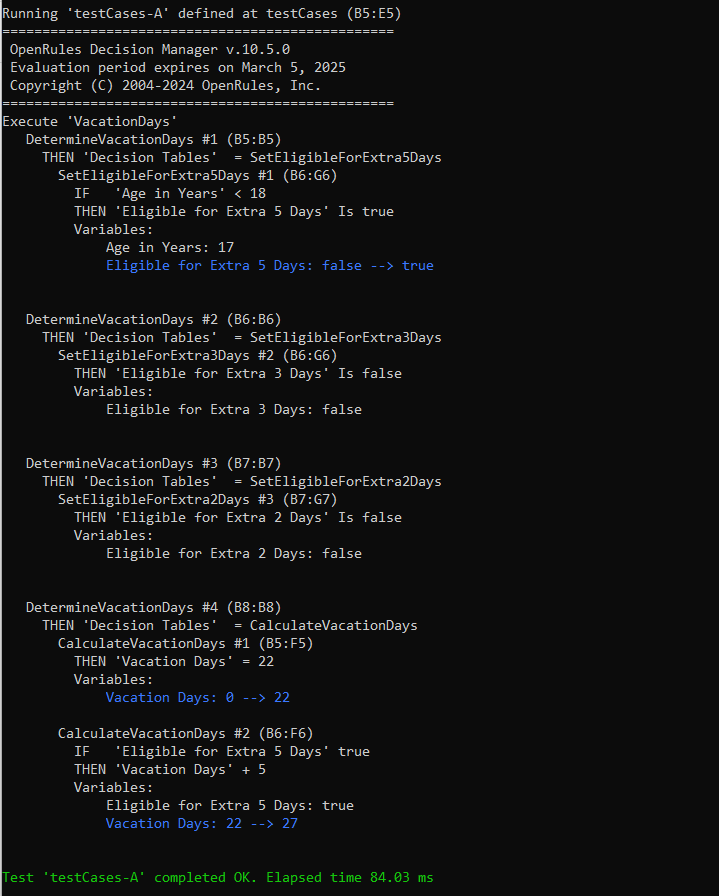

When you execute “test.bat” OpenRules validates all included files and if there are no errors it generates the correct Java code, and executes your tests. The results are shown in the execution protocol similar to this one:

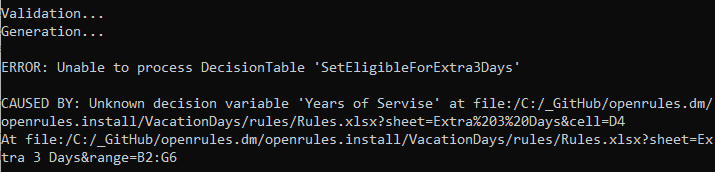

If OpenRules finds errors during the validation of your decision model, it will report error messages in a user-friendly format. Here is an example of the error message:

The error “Unknown decision variable ‘Years of Servise’ at <reference to Excel file>”. In this case, we made a mistake by typing ‘Years of Servise’ instead ‘Years of Service’ as this variable was described in the Glossary.

OpenRules makes all efforts to catch and report errors during the validation phase. However, when using Excel to create/modify tables a user has complete freedom and potentially may introduce some structural errors that violate OpenRules format requirements or mistakes inside Java snippets. In such rare situations, OpenRules might miss such errors and generate an invalid Java code in the folder “Target”. Then these errors will be caught by the Java compiler and reported in too technical format. Still, these error messages may give a hint of what was wrong and where.

To avoid errors, it is better to start with a small decision model without error messages. Whenever you make even small changes run “test.bat” to make sure you did not introduce errors. This way you will always know the source of your errors.